A Simple Explanation of Regression to the Mean

One concept I didn’t really “get” for a long time was regression to the mean. I think I have some intuition for it now though and — in the spirit of my other simple explanations thought I’d write it up here.

Explanation

Say you have a fair coin, and you flip it 10 times and count the number of heads.

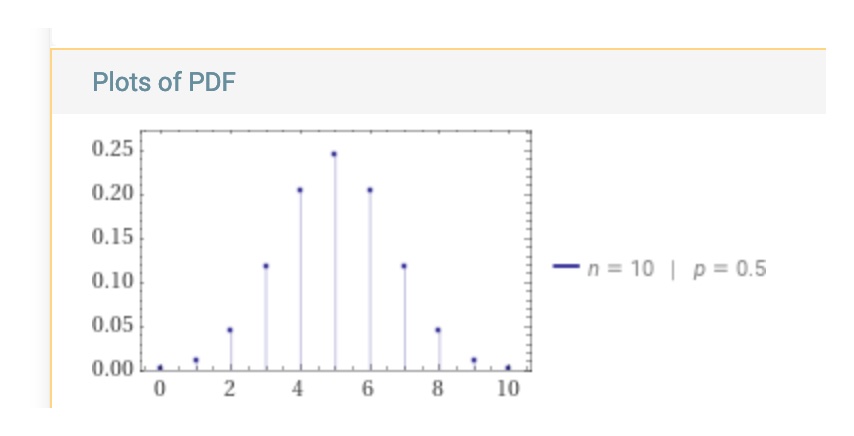

The number of heads in that 10 flips follows a binomial distribution which looks something like this:

There’s about a 4% you get 2 (or 8) heads, 12% you get 3 (7), etc.

Now get 1000 different people to do that same set of 10 flips with their own unbiased coins. Just because of how probabilities work, about 40 of the people will flip two heads, about 120 three, etc.

Regression to the mean just means that — if these “extreme” 2 heads people continue flipping their coins, the low probability of heads is unlikely to continue.

If you flip a coin 10 times — regardless of what happened before — there’s a 95% chance you’ll get more than 2 heads, and a 90% chance you get between 3-7 heads.

So if these forty 2-head flippers all flip another 10 coins, 90% of them will flip something closer to the mean.

That’s the key I think, recognizing “extreme” events as low probability events to begin with, and realizing that — if they really are low probability events and you continue drawing from them — you’re likely to see results closer to the mean.

This example is easier because we have a coin we know is fair and a bunch of events where we know some are bound to be extreme. In real life, with smaller samples and unknown distributions it’s harder because you don’t necessarily know if you got an extreme draw from your distribution, or whether the underlying probability is different from what you thought.

For example: in 2016 the US elected Donald Trump, who was an “extreme” candidate (probability-wise). Was that a fluke draw and should we expect a regression to the mean where the US (or GOP) selects a more traditional candidate next time? Or was it some underlying shift where the probabilities changed and it’s likely we see more of the same in the future? Hard to say.